Past, present, future - the tangible and intangible heritage of the Borneo longhouse

The ‘Head-Hunters’ longhouse’ is an attention seeking sales pitch for many arranged tours to Malaysian Borneo. With the reference to head-hunters seemingly capturing a sense of the ultimate exotic, the advertisements simultaneously work on several provocative notions/emotions including primitivism, past cultures, the scary thrill, and also something akin to romanticism. The latter is evoked through a sense of glimpsing a lost world. The tourism material, which typically arranges a visit or even an over-night stay or longer in a 'traditional head hunter longhouse', consistently refers to these places as tradition. They also routinely stress the special character of the houses and their remoteness (an ‘away from modern life ‘trope). They also explain that you will be instructed in the proper behaviour when entering the house so as not to offend the inhabitants, the indigenous people.

But what are Bornean longhouses? There is extensive ethnographic research from the early 20th century on these houses, and they are part of the ethnographic canon. There is also, of course, more recent sociological and anthropological research. Here, however, my gaze is on the Borneo longhouse as part of the region's heritage. To me, they provide an interesting case because it seems that the longhouse is heritage in a manner that interweave the tangible and intangible dimensions very tightly. It is also an illustration of the relevance of the concept of tradition, a concept that is often left out in the discussion of the intangible, as ‘traditional knowledge’ becomes one noun rather than two aspects.

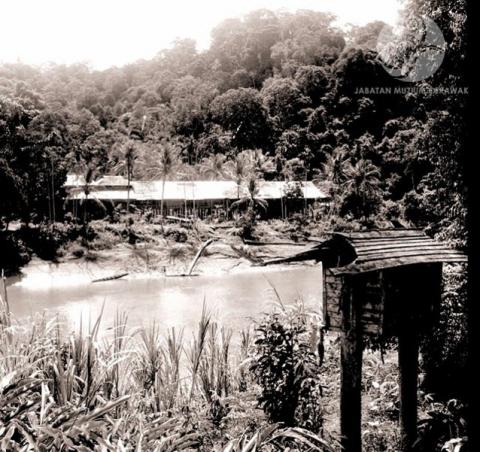

Figure 1: Long Jegan longhouse near the bank of the Tinjar river, 1956. Photograph from the archive of the Sarawak Museum

https://quod.lib.umich.edu/t/tapic/x-7977573.0004.102-00000008/1?subview=detail;view=entry

Figure 2a: A typical Orang Ulu longhouse; Fig. 2b: The shared communal area in the Orang Ulu longhouse (the Gallery [ruai]).

Sarawak Cultural Village (Photo M.L.S. Sørensen)

When I recently visited the area around Kutching in Malaysian Borneo I had the opportunity to discuss longhouses over a two week period with a few members of the Iban tribe. I was consistently struck by how they would refer to themselves and others as ‘belonging’, of being of, a named longhouse. It seemed to me that they were simultaneously referring to a specific physical building and to its residents/members, to membership – they were part of both and thus ‘belonged’ to the longhouse. This notion of belonging, moreover, was unaffected by whether they actually lived in the longhouse or lived somewhere else. Several interviewees explained that they would go home and visit regularly, some time for special events but otherwise, as far as I understood, just to reconnect and maintain the ‘belonging’. These visits to the longhouse were described as positive, revitalising, and necessary parts of the year/life. While in the longhouse, they would help with maintenance activities and live in a traditional manner and perform traditional practices. I also got the impression that these visits were not based on calendar events but were for personal reasons and available time and thus formed around a curious mix of responsibility and needs. For some, this would involve four to five hours of travel into remote parts of Borneo. Their accounts provided an interesting sense of the longhouse itself being thought of as a kind of kin. It is tempting, therefore, to assume that the longhouse represents the extended family (they often housed up to 100 people), both metaphorically and in terms of its inhabitants. This might originally have been the case, but it is not so anymore. Moreover, different interviewees had different notions of who could live together in the longhouse. One stressed it could be anyone irrespective of family ties as long as they shared the same religious belief (i.e. not Muslims); another explained that within his longhouse about 15 families were living together, all related to each other but some had converted to Islam, and the difference in beliefs was not a problem. Throughout these conversations the idea of the longhouse, although varied, emerged as an extremely strong expression of value and tradition and one that still had strong relevance today. It was a central, almost ingrained and naturalised, part of identity recognition and performance. I heard it expressed that “A longhouse is a way of life”, and that it was “a very good way of living, they have modern facilities but also the support of and sense of community”, and that “you are part of a longhouse”. Commensality, especially through feasts and traditional cooking, and community were stressed.

Figure 3: A modern concrete and brick longhouse near Matang Wildlife Centre (Kutching), Borneo (Photo M.L.S. Sørensen).

It is, however, not just the idea of longhouses as tradition and identity that pervades Malaysian Borneo (and especially its notion of indigenous culture). The longhouse tradition can also be seen as a strong influence on architecture and, I believe, urban planning. Some of this is subtle and would need detailed studies to fully identify and understand, but other influences are obvious. An example of this is the modern longhouses made of concrete, plaster, and bricks, but which in their layout and how co-habiting a space is organised follow the same principles as the traditional wooden ones. In such cases, there has been a total material transformation of the building, but its arrangement of sociability has been maintained. One may say that despite the tangible changes the longhouse as an organisational idea, and thus a tradition of living, continues. One of my interviewees lived in such a modern longhouse, see figure 3. In his reflection, his longhouse was not essentially different from a traditional one, just materially modern. It was also striking to compare the arrangement of the modern longhouse with the traditional one found in the Sarawak Cultural Village or those seen in old photographs (figure 4). All three versions have under one roof communal and private areas. The former takes the form of a communal gallery running along the whole length of the house and behind that is the separate private family rooms, which are all entered from the gallery. Whereas many elements would differ between the modern longhouse and the ‘traditional’ ones, such as washing machines and cookers, the structural layout raises similar opportunities as well as challenges in all the settings. Being 'under one roof' and explicitly referencing the very idea and tradition of longhouses, the modern concrete longhouse still provides a sense of community, of being part of and of ‘belonging’ to a particular longhouse, and my interviewee referred to his house in that manner. He also stated that it is a longhouse “because people say it is.” At the same time, this form of community, whether in a traditional wooden house or a modern one, needs to have forms of consensus building to manage tensions, for example, between the communal and private spheres. This traditionally was the role of the chief of the longhouse. Life within the modern longhouse is still organised through such structures of power and decision making, and the longhouses fall under the responsibility of, or give rise to, local chiefs. The greatest changes from the traditional wooden longhouses are, therefore, probably neither found in the materials nor in the spatial arrangements but rather in how very traditional forms of localised power structures (the chief) now have to be accommodated within other levels of social and political powers and decision making. Now, when removing garbage is organised by the municipality, the chief has little say over how it is done!

Figure 4a-c: The long communal area (the gallery) in, left, an Iban longhouse in Sarawak Cultural Village, middle, a modern longhouse near Matang, and right, a Kayan longhouse at Long Lama from around 1912.

(Fig. 4a and 4b photo: M.L.S. Sørensen, Fig. 4c from Hose, C. and W. McDougall 1912).

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank all those who freely shared their reflections on their longhouses with me, in particular Dominic Kelndek and Richard (surname unknown).

Reference

Hose, C. and W. McDougall 1912. The pagan tribes of Borneo; a description of their physical, moral and intellectual condition, with some discussion of their ethnic relations. London: Macmillan.