Commemorating South Korea's Cheju April 3rd Incident: Cultural Trauma and the Politics of Postmemory

By Seong-nae Kim (Professor Emeritus, Sogang University, Korea)

The Cheju April 3rd Incident: State Violence and Trauma

The genocidal legacies of the 20th century had established the global Cold War system in the new nation-states in the Asia-Pacific region, a geographic zone that experienced turbulent decolonization, which often involved civil wars and other forms of political violence, unlike the transatlantic experience of the Cold War. This article enquires into questions of state violence and inter-generational transmission of traumatic memory with respect to the Cheju April 3rd Incident (1947-1954), which is regarded as the precursor of the Korean War, one of the first outbreaks of the violent ideological conflict during the global Cold War.1

Historically and politically, Cheju Island, which is located on the periphery of the Asia-Pacific and the Cold War, has been considered a site of strategic importance, and, hence, has had a continued military presence over the years. At the end of the Pacific War, Cheju was set up as the frontline of the Japanese militaries in their defense against the American landing. After the World War II, Cheju was under the authority of the American occupation government (1945 -1948).

The Cheju April 3rd Incident is known as the ‘4.3 Incident,’ or sasam sakon, which is named after the date of its initial occurrence on April 3rd in 1948, when the island branch of the South Korean Worker’s Party (SKWP) guerrillas began armed uprisings against occupying American forces. In fact, this uprising event stemmed from the March 1st, 1947 civilian gathering originally for memorializing Korean March 1st Independence Movement, but it changed into civilian demonstrations opposing increased taxation, rice shortage, and the oppression of local autonomous People’s Committee by the American military government police, who eventually fired on the unarmed protestors, killing six and wounding eight. In the aftermath, radical leftists forces sought armed attacks against police and rightwing youth stations on April 3rd, 1948.

Figure 1: “Before a rebel slaughter as the rebellion began. An American adviser, Lieut. Ralph Bliss, looks on silently where no advice will help.” Source: LIFE Magazine, 15. Nov, 1948.

The insurgency then erupted into a civilian massacre, and more precisely, a planned act of state terrorism “screening operations” and house-to-house searches as part of a suppressive counterinsurgency campaign, with the support of American military aid, to weed out so-called “reds.” Most victims of this counterinsurgency campaign were local civilians with no affiliation to any ideological position. After the establishment of the anticommunist state in South Korea on August 15th, 1948, the violent events of civilian massacres continued through the Korean War period (1950 – 1953) and officially ended after the prohibition against entry into the Mount Halla area was lifted in September 21st, 1954.2 Lasting for a total of seven and half years (March 1947- September 1954), the Cheju April 3rd Incident resulted in a massive death toll of 30,000 (nearly one-tenth of the entire island population) and the destruction of one-third of the 300 village communities under suspicion of communist collaboration. The 4.3 Incident and the Korean War are linked to the evolution of the longue durée of America’s informal global empire.

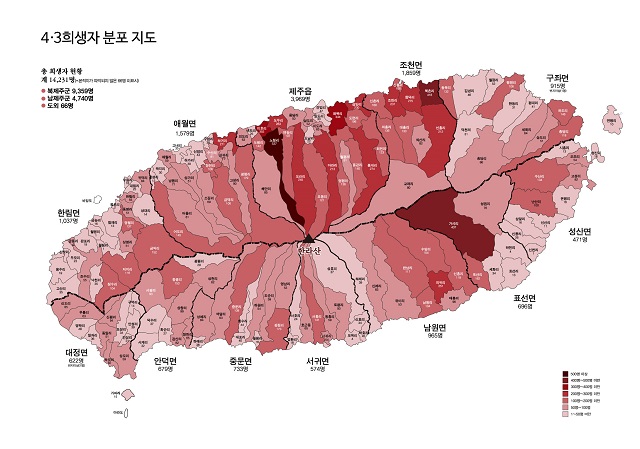

Figure 2: Map of Victims of Cheju 4.3.Total registered victims: 14,232 (as of 2017). However, the number of victims estimated by the Cheju April 3rd Incident Committee is 25,000 to 30,000. Source: the Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation

The effects of the catastrophic events of the 4.3 on collective consciousness and cultural identity could be defined here as “cultural trauma” in Jeffrey Alexander’s term.3 Cheju people often express such a tragic sense of history that “all accumulations had disappeared and also their lives ruined.” The new generations were disconnected from their past. Following the division of Korea, the anti-communism of the South Korean state effectively suppressed the memory of the civilian massacre and its aftermath for over half century until the liberal administration of President Kim Dae-jung established its first truth commission in 2000.

Postmemory and Ritual Mediations: Shamanic Public Rite for Healing Trauma

Two decades of democratization and transitional justice advocacy movements successfully resulted in the enactment of the Special Law for Truth Fact-Finding and Recuperation of Honor to Victims of the Cheju April 3rd Incident in 2000, and formulated officially what is today called “the 4.3 memory.” Ongoing commemorative public projects have been realized through regular memorial ceremonies, a memorial park, memorials at the massacre sites, and also public shamanic ritual for consolation of the dead victims of the 4.3. Alongside these public memorial events, there exist the personal and family domains of “the 4.3 memory.” Despite the current evolution and official sanction of “the 4.3 memory”, a divergence between national official memory and family individuated memory emerged. This divergence occurs in the hierarchical spectrum of scales of the 4.3 memory: family, local community, and the state. They create a collective genealogy as agencies of transmission of the 4.3 trauma. There exists the paradoxical demand of the perspective of victims to be accorded a place within national memory for the sake of official recognition.

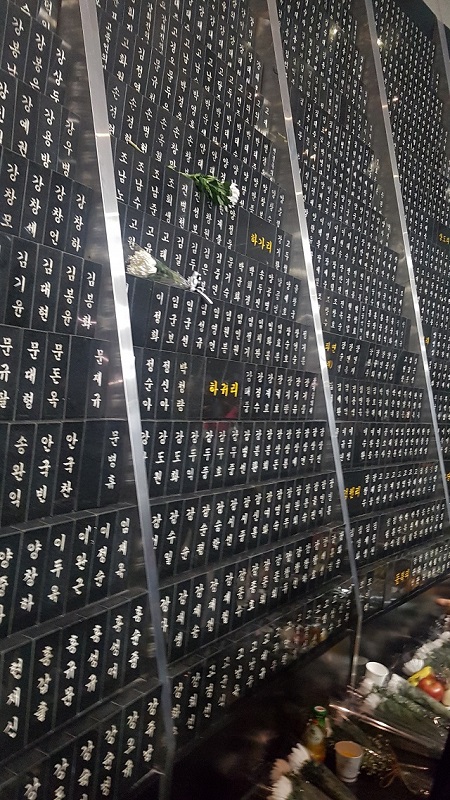

Figure 3: Prayers at the wall of tablets inscribing the names of the estimated 15,000 victims in Cheju 4.3 Peace Memorial Park which opened in 2008

In this context, I examine the ways in which this divergence is mediated in ritual practices of shamanic spirit possession and kinship rites of reburial of victims’ dead bodies that were exhumed from mass graves at the Cheju Airport in 2008 sixty years after the massacre. These ritual forms “contain the particular mixture of mourning and repair of trauma that characterizes the work of postmemory.” Drawing on Marianne Hirsch’s concept of “post-memory,” I explore the transmission of the 4.3 memory of a generation of Cheju people who have grown up dominated by testimonial narratives and ritual accounts of events that have persisted into the present.4

Prior to public commemoration activities in the 1990s, shamans had played a pivotal role in expressing cultures of emotions and trauma that had been otherwise hidden for several decades. Initially held in near secret and at private homes, their family-based rituals of spirit possession have now become the vehicle for mass-scale public memorialization in the present. Performing spirit possession and chanting laments of the dead (young-gye ullim), the shamanic ritual dramatizes “the presence of the past in the present” in such a way that the victims of violent past events become beneficent ancestral agents who bring social justice and prosperity to a post-generation. This might be the pragmatic politics of spirit possession ritual. Together with the civilian-led National Artists Federation, the Cheju shamans annually performed public rituals of commemorating the victims at massacre sites since 2002. These rituals are called the "Cheju 4.3 Shamanic Ritual for the Resolution of Grievances and the Mutual Beneficence" (Cheju Sasam Haewon Sangsaeng Kut).

Figure 4: The 4.3 Haewon Sangsaeng-kut near the excavation site where the remains were discovered in the mass burial at Cheju Airport in 2009. Photo by the author.

Exhumation of Mass Graves: Place-making of the Dead

In April 2009, the shamanic public ritual for commemoration of the 4.3 victims was held at the secret mass grave near Cheju Airport runaways, which was excavated for 2 years from 2007 to 2009. The target groups of the official exhumation of mass graves were the "missing victims." Secretly buried underneath the airport runway, the victims' bones were exhumed more than sixty years after the event. In the case of this second exhumation project (2008 -2009), most of the dead exhumed were known to be civilian prisoners who had been convicted of crimes (i.e. espionage and engaging in enemy liaisons) by court martial in June and July 1949.

In Oct 2007, after the first excavation of the remains, an on-site funeral and ancestral rite for the hundreds of victims were performed.6 Here we witness how the exhumed bones serve as affective mediations of violence and memory. From the exhumation to the enshrinement of remains, the processing of repatriating the dead to the family and the community “animates” the post-memorial politics of the 4.3 memory, as well as localized contestations over belonging (e.g. personhood, kinship, placement).7 The exhumed bones embody the traumatic memory of mass killing in addition to its oppressive forgetting in history. After more than sixty years of forgotten history, those missing dead who had previously been labeled "insurgents" (pokto) were now recognized as “victims” (hwisaeng'cha) who were illegitimately sacrificed state subjects.

Figure 5: The Bereaved Families’ collective funeral and ancestral rite for the April 3rd victims whose remains were excavated after 60 years’ disappearance, in front of mass grave at the Cheju Airport in Oct 2nd, 2007. Photo by Yang Joohun, Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation.

More than this, they have further acquired new identities of “heroic souls,” (young- ryoung), a form of moral recognition that would be politically sanctioned by the state. Through these new identities, they are now eligible for official commemorations. This ‘ritualized hospitality’ toward these new collective dead - what Heonik Kwon would call “political ghosts” - exceeds the morality of traditional kinship structure and operates in variant forms of kinship ritual such as funeral and ancestral rite at the massacre sites.8

However, we may further observe powerful and painful shifts in remembering the dead and their intersection with broader political shifts in the scale of social relations with the dead. The fragmented and interiorized nature of vernacular memory work reveals both the domineering nature of national memory and the paradoxical demand that the perspective of victims be accorded a place within national memory for the sake of official recognition.

Figure 6: The Pukchon village 4.3 memorial monument and stele engraved on the names of 443 victims who were massacred in a single day in January 1949. On the top of the memorial monument, the national flag and flower is engraved as if the state protects the its people. Photo by author.

New Paradigm of Postmemory for Reparation and Social Repair

The ancestral veneration in the post-April 3rd Incident era could be termed a “ritual of reconvening”, to draw together the dead and the living pulled apart by the mundane and extraordinary demands of the world beyond the home. However, social conflicts over the qualification of legal “4.3 victims” and social stigmatization of the “red insurgents” (pok’to)” resurge constantly in the postmemory regime. The ‘insurgents’ would not be welcome to kinship genealogy, and also their names listed initially as ‘4.3 victims’ would be erased under an accusation of “delinquent tablets” in the public memorial hall at the Cheju April 3rd Peace Park. In spite of their social alienation and historically liminal status, such non-aligned spirits of ‘the insurgents’ might be the right object of the proper ancestral veneration that attests to the new paradigm of memory politics in which all dead are equally and permanently revered, regardless of identity.9 In the Picture 3, it is noticeable that the names of so-called “delinquent tablets” are erased after conflicts over the proper ‘victim’ status of former armed guerrrilas to be unable to get enshrined together with the other tablets of civilian victims.

This new kind of concern for all victims of the violent past places the issue of suffering at the heart of public, common concern. In The Empire of Trauma, Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman suggest that concern for the victim is a sign of human society. It is because trauma, in their words, has “descriptive value, but more importantly prescriptive value, calling for action (clinical, economic and symbolic) and reparation.10 Recognition of trauma leads to the politics of reparation. In the politics of postmemory, all victims become culturally and politically respectable, and trauma itself becomes an unassailable moral category.

For the surviving descendants of victims of the Cheju massacre, however, the politics of memory and place-making of the dead is an incomplete and ongoing question. The question of ownership and belonging regarding the remains of the 4.3 massacre continues to be an issue today. While descendants of the deceased appreciate the official recognition of the violent deaths of their kin, in the process of these deaths being made public, the question of ownership over the dead and their memory, in the form of where these remains ought to ‘placed’ – whether in private family cemeteries, in public memorial parks – but also to whom knowledge of these deaths ought to be made accessible, continues to be contested in the post-Cold War worlds.

1. Bruce Cumings, 1990, The Origins of the Korean War, Volume II: The Roaring of the Cataract: 1947-1950, Princeton University Press, p.251

2. The definition of the April 3 Incident is officially granted in this way according to Cheju 4.3 Sakŏn Chinsang Kyumyŏng mit Hŭisaengja Myŏngye Hoebok Wiwŏnhoe, Cheju 4.3 Sakon Chinsang Chosa Pogosŏ [The Cheju April 3 Incident Investigation Report] (in Korean), 2003. Published in 2003, this is the first report of the massacre authored by the National Committee for Investigation of the Truth about the Cheju 4.3 Incident [or the "Cheju Commission"]. In 2000, the South Korean National Assembly had established special legislation for opening the investigation of the Cheju April Incident. In 2013, translations of the report into foreign languages such as English, Japanese, and Chinese were made available by the Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation. All translations as well as the original Korean version of the report may be found on the website of the Cheju 4.3 Peace Foundation: www.jeju43peace.or.kr.

3. Jeffry Alexander et al ed, Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity (Berkley:University of California Press, 2004), p.1.

4. Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012).

5. Seong Nae Kim, “The Work of Memory: Ritual Laments of the Dead and Korea's Cheju Massacre,” in A Companion to the Anthropology of Religion, eds. Janice Boddy and Michael Lambek (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2013)

6. After this ritual, the bones were moved to the laboratory of forensic medicine at Jeju National University in order to conduct forensic examination and DNA tests. These tests were conducted to match the victims' bodily remains with their respective bereaved families. The exhumed bones were kept in cinerary urns after cremation and enshrined in a special commemoration hall within the Cheju 4.3 Peace Park. Only 48 cases out of 259 remains could be identified with personal names. The cinerary urns of the dead whose personal identities were confirmed were then labeled with their personal names and their descendants' addresses. Having regained their personal identity, the dead could eventually be returned to their home.

7. Katherine Verdery, The Political Lives of Dead Bodies (New York: Columbia University Press, 1999)

8. Heonik Kwon, “The Ghosts of War and the Ethics of Memory”, in Ordinary Ethics, ed. Michael Lambek, (New York: Fordham University Press, 2010), 400-413.

9. Seong Nae Kim, “Placing the Dead in the Postmemory of the Cheju Massacre in Korea,” Journal of Religion 99(1): 80-97. Jan 2019. University of Chicago Press.

10. Didier Fassin and Richard Rechtman, Empire of Trauma: An Inquiry into the Condition of Victimhood (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 153.