The contested gazes of ‘Comfort Women’ statues in Korea and Taiwan

by Hyun Kyung Lee and Shu-Mei Huang

Gaze 1 in Seoul

Since December 2011 the gaze of a ‘comfort women’ statue, called the ‘Statue of Peace’, has been directed at the Japanese Embassy in Seoul (photo 1). This first ‘comfort women’ statue was erected in front of the Japanese Embassy by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (the Korean Council), to celebrate the 1000th weekly Wednesday Civic Rally calling on the Japanese government to issue an official apology and compensation to the Korean victims of the Japanese army’s Second World War sexual enslavement.[1] The sculptors creating the statue, Kim Un-sung and Seo-kyeong, embodied ‘comfort women’ in the form of an unsmiling girl frozen in time as a teenager, at the age when she was forced into sexual slavery. Koreans sees this statue as a representative of comfort women and for many it seems to evoke their empathy for ‘comfort women’s pain and trauma.

Since December 2011 the gaze of a ‘comfort women’ statue, called the ‘Statue of Peace’, has been directed at the Japanese Embassy in Seoul (photo 1). This first ‘comfort women’ statue was erected in front of the Japanese Embassy by the Korean Council for Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan (the Korean Council), to celebrate the 1000th weekly Wednesday Civic Rally calling on the Japanese government to issue an official apology and compensation to the Korean victims of the Japanese army’s Second World War sexual enslavement.[1] The sculptors creating the statue, Kim Un-sung and Seo-kyeong, embodied ‘comfort women’ in the form of an unsmiling girl frozen in time as a teenager, at the age when she was forced into sexual slavery. Koreans sees this statue as a representative of comfort women and for many it seems to evoke their empathy for ‘comfort women’s pain and trauma.

For a long time, the stories of ‘comfort women’, who were forced into sexual slavery at front-line Japanese military brothels during wartime, were deliberately forgotten, as negative and shameful wartime legacies, by the male-dominated society. However, in 1991 the lone and weak voice of a single surviving ‘comfort woman’ broke this long period of silence, providing the momentum for the articulation of other comfort women’s stories with support from Korean, Asian, and global NGOs. Their voices have been amplified through weekly Wednesday Demonstrations, documentary films, literature, paintings, and songs. In turn, at a global level, their painful and traumatic memories have formed a grand narrative concerning human rights, war crimes, and gender history. The Seoul ‘comfort women’ statue has thus become an icon of ‘comfort women’s stories’ more widely, and – through the active efforts of a transnational movement – the statue has been replicated globally in other cities in Korea, Taiwan, China, other Asian countries, the U.S., and Australia.

Japan’s government, in light of the first statue’s symbolic location and the efforts of civil organisations worldwide, perceives the statue as a diplomatic weapon used by Korea on the international stage to damage Japan’s image, and has since a 2015 Japan–Korea agreement on ‘comfort women’ issues officially urged its dismantlement. This agreement was rejected not only by the Korean Council and surviving comfort women but by trans-national civil groups; volunteers determined to prevent the statue’s demolition take turns to maintain 24-hour vigils beside the statue (photo 2). This first ‘comfort women’ statue’s gaze seems to be trapped in the Japan–Korea diplomatic relationship.

Gaze 2 in Tainan

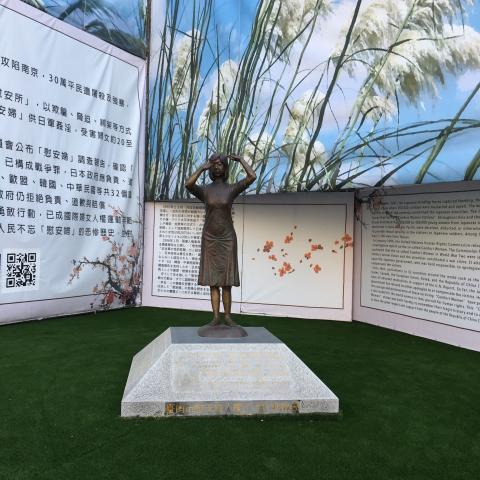

The transnational movement in support of comfort women found echoes in Tainan, the cultural capital of Taiwan, a former colony of Japan. There the first ‘comfort women’ statue was erected on 14 August 2018, during the “Memorial Day for Japanese Forces’ Comfort Women Victims” recently instituted by South Korea (photo 3). The statue, standing 160 centimetres tall, shows her resistance through her raised arms. This statue was built by a non-profit group, the Tainan Association for Comfort Women’s Rights, without involvement from the Taiwanese government. Yet Taiwan’s former president, Ma Ying-Jeou, now still a senior member of the KMT (Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party) participated in the ceremony, and called on Japan to issue an apology and provide reparations for its wartime actions. Subsequently, Japan’s de facto embassy in Taiwan requested the removal of the statue, which was in September 2018 subjected to a deliberate act of vandalism by an individual representing 16 right-wing groups from Japan.

The transnational movement in support of comfort women found echoes in Tainan, the cultural capital of Taiwan, a former colony of Japan. There the first ‘comfort women’ statue was erected on 14 August 2018, during the “Memorial Day for Japanese Forces’ Comfort Women Victims” recently instituted by South Korea (photo 3). The statue, standing 160 centimetres tall, shows her resistance through her raised arms. This statue was built by a non-profit group, the Tainan Association for Comfort Women’s Rights, without involvement from the Taiwanese government. Yet Taiwan’s former president, Ma Ying-Jeou, now still a senior member of the KMT (Kuomintang, the Nationalist Party) participated in the ceremony, and called on Japan to issue an apology and provide reparations for its wartime actions. Subsequently, Japan’s de facto embassy in Taiwan requested the removal of the statue, which was in September 2018 subjected to a deliberate act of vandalism by an individual representing 16 right-wing groups from Japan.

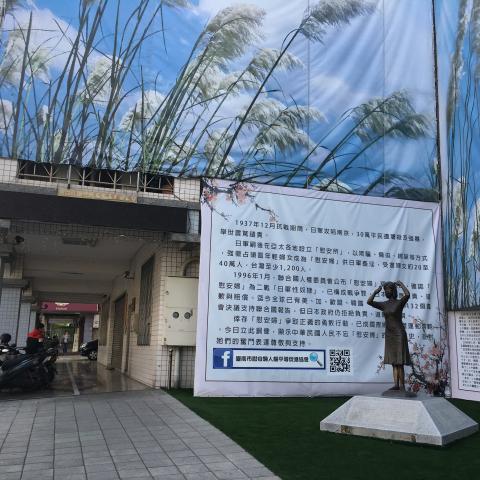

On the surface, the erection of the ‘comfort women’ statue in Tainan can be interpreted within the context of diplomatic conflicts between Taiwan and Japan. However, this statue’s location implies further stories behind the scenes: the ‘comfort women’ statue is situated in the city centre, right next to the KMT’s Tainan chapter office (photo 4). Although the statue was erected by a civil group, the group’s leader was a former KMT affiliate, and the KMT gave permission for the statue’s erection on a small empty lot adjoining its office. Through this erection, the KMT denounced the current ruling party, the DPP (Democratic Progressive Party), for shying away from examining the painful history of Taiwan under Japanese rule (including comfort women) as the current Tsai administration has actively strengthened its relationship with Japan, hoping to cultivate trade possibilities against a backdrop of China’s growing economic dominance in the region. The KMT had used the statue’s erection to raise the party’s profile ahead of local elections, as the party has tried hard to distinguish itself from the DPP in its hostility towards the colonial history under Japan and, by extension, in its persistence in seeking unification. It may be fair to say that this statue’s erection is embedded in partisan conflicts and competition between the KMT and the DPP much more than diplomacy between Taiwan and Japan.

It is also interesting to note that across the street from the ‘comfort women’ statue stands the five-story Hayashi Department Store: one of Tainan’s most symbolic and historic Japanese colonial architecture sites, in a commercial district that was considered the “ginza of Tainan” (photo 5). This department store, built in 1932, was in 1998 recognised as a Municipal Heritage Site; it reopened in 2014 and has become an attraction to both Taiwanese visitors and Japanese tourists. The case thus exemplifies Taiwan’s selective favouring of the Japanese colonial legacy as having brought about a culture of modernity during the inter-war Taishō-Showa period. Reflecting this context, the ‘comfort women’ statue’s gaze in Tainan is fluctuating between dark and painful war crimes and bright and selective appreciation of colonial memories in Taiwan.

|

|

Contested gazes of comfort women’s statues: from the place of remembrance to the place of amnesia

The erection of ‘comfort women’ statues has proven a watershed in transforming the comfort women’s shameful and negative memories from loci of forgetting into foci of remembering. According to the formation of a grand narrative of ‘comfort women’, the tangible icon of the ‘comfort women’ is centred in political struggles, and its symbolic meaning seems to be strengthened by where this statue is erected. Also, it is interesting to note that as the ‘comfort women’ statues have been increasingly politicised, the civic groups’ activities relating to ‘comfort women’ issues have diversified to reflect different purposes. For example, the civic group behind the Tainan ‘comfort women’ statue is not related to those Taiwanese groups, such as the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, pursuing international solidarity for comfort women in Taiwan. Similarly, hidden differences if not totally disagreements exist within the advocacy for comfort women in Korea. Although the Korean Council is the focal advocate group for ‘comfort women’, there is a separate civic group seeking the inscription of ‘comfort women’ into UNESCO’s Memory of the World register.

Along with the statues of ‘comfort women’ receiving particular attention, memory conflicts and diplomatic issues too have taken on its own life. Under the political shadow, ironically, the varied stories and individual memories of ‘comfort women’ tend to be neglected and seem to be transformed into places of amnesia. In the process of raising world-wide awareness of ‘comfort women’ issues, the gazes of ‘comfort women’ statues have been directed towards Japan, towards male-dominated society, and towards furthering political power. Now, it is timely for us to directly face their gazes with a reflection on hope and justice, which is the original intention behind creating ‘comfort women’s statue’ as a symbol of oppression. Responding to their gazes, we may want to pay more attention to surviving comfort women and their stories to help them find genuine peace and healing and to understand how we as part of the society could avoid repeating the wrong deeds involved in making them subjects to war violence. Instead of facilitating political struggle of all kinds, their gazes, hopefully, will contribute to solidarity with those who are suffering from oppressive memories and to restore their dignity and justice.

Along with the statues of ‘comfort women’ receiving particular attention, memory conflicts and diplomatic issues too have taken on its own life. Under the political shadow, ironically, the varied stories and individual memories of ‘comfort women’ tend to be neglected and seem to be transformed into places of amnesia. In the process of raising world-wide awareness of ‘comfort women’ issues, the gazes of ‘comfort women’ statues have been directed towards Japan, towards male-dominated society, and towards furthering political power. Now, it is timely for us to directly face their gazes with a reflection on hope and justice, which is the original intention behind creating ‘comfort women’s statue’ as a symbol of oppression. Responding to their gazes, we may want to pay more attention to surviving comfort women and their stories to help them find genuine peace and healing and to understand how we as part of the society could avoid repeating the wrong deeds involved in making them subjects to war violence. Instead of facilitating political struggle of all kinds, their gazes, hopefully, will contribute to solidarity with those who are suffering from oppressive memories and to restore their dignity and justice.

[1] Regarding the ‘comfort women’s legal compensation and formal apology, in 1994, the Japanese government set up the public-private Asian Women’s Fund (AWF) to distribute compensation to South Korea, the Philippines, Taiwan, the Netherlands, and Indonesia. Some former Korean comfort women received the fund, but many of them rejected the compensations on principle – although the Asian Women's Fund was set up by the Japanese government, its money did not come from the government but from private donations, hence the compensation was not "official" and was dissolved in 2007. In 2015, although Japan and Korea made a $9 m compensation agreement to form ‘the Reconciliation and Healing Foundation’. However, this compensation was denounced as it did not address the issues of whether coercion of the women was a policy of imperial Japan, and the ‘comfort women’ was excluded in the agreement. Therefore, this foundation was disbanded in 2018.