J. Eva Meharry:

Reconstructing the Bamiyan Buddhas

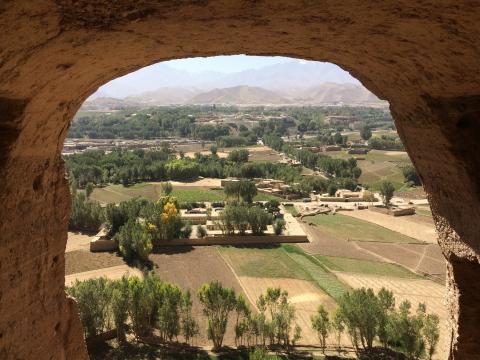

Standing at the foot of the Bamiyan Cliffs in Central Afghanistan on my fieldwork last summer, gazing up at the niche where the large Bamiyan Buddha once stood, my Afghan guide lamented the destruction of his country's heritage. In 2001, the Taliban famously destroyed the two Buddha statues, which had survived the rise and fall of empires for nearly fourteen hundred years along the ancient 'Silk Road'. The colossal standing Buddha statues were an impressive 55 metres and 38 metres tall, which were carved into two richly decorated niches in the Bamiyan Cliffs. The niches were surrounded by a 'honeycomb' of some 750 manmade caves, many of which boasted elaborate frescoes and sculptures.

Figure 1 View of the Bamiyan Cliffs and empty Buddha niches

When Bamiyan entered European consciousness in the nineteenth century, they were celebrated as one of the great ‘wonders of the world’. Following the advent of the archaeological discipline in Afghanistan in the early twentieth century, the selection of Bamiyan as a site of exploration and excavation by French archaeologists was fait accompli. As one of Afghanistan’s most prominent archaeological sites, Bamiyan was at the forefront of archaeological development through much of the twentieth century, beginning in the 1920s with surveys and excavations, and displays in the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul, followed by preservation work in the 1960s.

Figure 2 View of Bamiyan Valley from the niche of the small Buddha statue

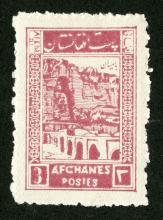

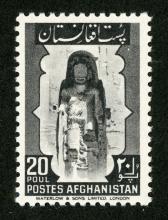

As demonstrated in my PhD research, Bamiyan was highly politicized by successive Afghan governments throughout the twentieth century. Following Afghanistan’s ‘independence’ from British control of the country’s foreign affair as a result of the Third Anglo-Afghan War of 1919, archaeological discoveries at Bamiyan were used by the Afghan government to assert the country’s autonomy and territorial boundaries, as well as national prestige as an ancient and glorious civilization, in the world order. Depictions of Bamiyan on state sponsored material, such as postage stamps and currency, were deployed in a similar vein.

In turn, the site became immersed in internal political turmoil. As an example, in 1932 and 1951, depictions of the large Bamiyan Buddha on postage stamps were protested by the conservative Islamic faction of Afghan society, which viewed the statues as un-Islamic. In both cases, the Afghan government revoked the issue within three months in order to quell discontent (Bonatz 1933, 321-323; Patterson 1964, 51-53; Uyehara & Dietrich 1995, 151-152).

Figures 3-4: 1932 3-Afghanis 'Bamian' postage stamp in the First Definitive Monuments Series; 1951 20-poul Bamiyan postage stamp in the Second Definitive Monuments Series. Images courtesy of Smithsonian Institution, National Postal Museum.

Several decades later, when the Taliban regime came to power, they initially also used Afghan cultural heritage for their political agenda. Following the chaos and carnage of the Soviet occupation and Mujahideen civil war (1979-1996), the Taliban made efforts to preserve and protect the country's heritage sites, including Bamiyan, as a sign of regaining control of the country (i.e. SPACH 2000, 17). Then, in a dramatic policy reversal in 2001, the extremist branch of the Taliban destroyed the two Buddha statues to assert their political agenda against the international community, which had failed to grant the government official recognition and provide aid for the country's famine, amongst other issues.

Today Bamiyan is a 'negative heritage' site, one which holds negative memories in the collective imagination (Meskell 2002, 58). It is therefore important to understand what circumstances led to the destruction of the Buddhas, not only in recent history, but over the longue durée, in order help understand what role the site may play in the future of Afghanistan. This issue has become all the more poignant in recent years. Since the designation of the Bamiyan Buddhas and surrounding cultural landscape as a World Heritage Site in 2003, a central question asked by the heritage community is whether to reconstruct the site. Initially, the Afghan government and UNESCO rejected suggestions out of hand at the international seminar on the 'Rehabilitation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage' in 2002, recognizing that international assistance should be focused on more critical, basic needs for war-exhausted Afghans (Manhart 2006, 50). However, as international assistance began to wind down more than a decade later, the Afghan government reversed their position, making a request for the reconstruction of one of the Buddhas at the 2016 World Heritage Committee session.

In September 2017, my supervisor, CHRC's Professor Marie Louise Stig Sørensen, and I attended the UNESCO conference, 'The Future of the Bamiyan Buddha Statues: Technical Considerations and Potential Effects on Authenticity and Outstanding Universal Value', in Tokyo. Four primary proposals were presented at the conference, most notably a plan to reconstruct the monuments from their original fragments by a process called anastylosis (Petzet 2009, 46). Such a plan faces a number of obstacles, from the unstable condition of the caves to the exorbitant cost of the undertaking. Critics most notably argue whether any reconstruction should be undertaken while Afghanistan remains an active conflict zone, with the Taliban controlling a majority of the country's territory outside the capital of Kabul, recognizing that the country is not the 'post-conflict' zone cited by international organizations.

Following the Tokyo conference, the next step is for an Afghanistan-based working committee to make further recommendations to the Government of Afghanistan and the World Heritage Committee; recommendations that should incorporate various stakeholders' views in order to comprehensively assess the potential impact the rehabilitation of the Bamiyan Buddhas will have on Afghanistan's economy, society and identity.

Unless noted otherwise, all photographs are taken by the author.

References

Bonatz, E. 1933. Afghanistan: Legendary Locality of the Biblical Paradise and the Landing of the Ark. The New Southern Philatelist, 9 (10), 321–323.

Manhart, C. 2006. UNESCO's Rehabilitation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage: Mandate and Recent Activities. In Art and Archaeology of Afghanistan: Its Fall and Survival, edited by J. van Krieken-Pieters, 41-60. Leiden, Brill.

Meskell, L. 2002. Negative Heritage and Past Mastering in Archaeology. Anthropological Quarterly 75 (3): 557-574.

Patterson, F.E. 1964. Afghanistan: Its Twentieth Century Postal Issues. New York, The Collectors Club.

Petzet, M. 2009. The Giant Buddhas of Bamiyan: Safeguarding the Remains. Berlin, ICOMOS–Hendrik Bäßler Verlag.

SPACH. Decrees by Mullah Omar. Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage Newsletter, 2000: 17.

Uyehara, C.H. and Dietrich, H.G. 1995. Afghan Philately: 1871–1989. Santa Monica, George Alevizos.