Andrea Kocsis:

Interpreting the site of a 700 years old massacre

Today the Clifford's Tower is one of the main tourist attractions in York managed by the English Heritage. The pretty medieval keep standing in the heart of the city is charming with its clumsily leaning walls and with the peaceful families of geese living around it. Apart from one table in the bottom of the hill, nothing gives away that the Clifford's Tower is a place of dissonant heritage. However, it is actually a dissonant heritage site, since one of the worst anti-Semitic massacres of the Middle Ages took place here in 1190.

That time the Jews experienced numerous attacks and anti-Semitic riots throughout England. When the Sheriff of York had left for the Third Crusade, a fire broke out in the city. During the chaos, some citizens of York formed an angry mob against the local Jews. As a response, Joceus, one of the most prominent Jews of York, led the city’s Jews to seek protection from the keeper of the King’s tower inside the castle. The constable, as the employee of the King, offered his protection, and that way the city’s entire Jewish community was trapped inside the keep standing on the spot of the present Clifford's Tower. When the constable was called on other duty and had to leave the tower, the trust between the Jews and the keeper broke down, and they refused to allow him back in. With this act they challenged the king’s authority, therefore the constable's troops joined the mob outside against the Jews.

It was Friday 16 March, Shabbat Hagadol, the ‘Great Sabbath’ before the Jewish festival of Pesach or Passover, when the Jews realised that they could not hold out against the siege. The community trapped inside the keep decided to die together, instead of waiting to be killed or forcibly baptised. They set fire in the timber keep to let their possessions they had brought with them be destroyed. Then before taking their own life, the fathers of each family killed their wife and children. Those who chose not to commit suicide and survived the fire, were killed by the attackers the next morning. About 150 Jews, 20-40 families died during the night of the 16th-17 of March in 1190.

After the massacre, a new Jewish community established itself in York for an other 100 years, when Edward I expelled all Jews from his kingdom. They could return only in the 17th century. Regarding the site itself, the fire consumed the timber tower, the and currently visible stone keep was built 60 years after the massacre.

Although this horrific story is painful, heart-breaking and important for understanding a bigger picture in the history of anti-Semitism, the site and its use stands in contrast with this shortly presented episode of its past, which makes the Clifford's Tower a contested heritage site.

The English Heritage does not put a focus on the massacre in the official interpretation of the site. However, their attempt has changed over the years, since Prof David Uzzell complained in the following way: 'At the time when the first study was written the interpretation of Clifford‟s Tower in York did not just minimise the history but failed even to tell the story of the "ethnic cleansing" of the Jewish population of that city(...) The interpretation of the Tower's history focused on who had lived there, its changing role over the centuries and its building materials, but no mention was made of the fact that the Jews of York were corralled into the Tower, and when faced with annihilation, committed suicide.' (Uzzell and Ballantyne, 1998: 165).

Today inside the tower there are still no panels detailing or interpreting the massacre. However, in the official tourist guide book the events are described in two pages. The narrative and the illustrations of the booklet manages to insert the story into the wider picture of Jewish history.

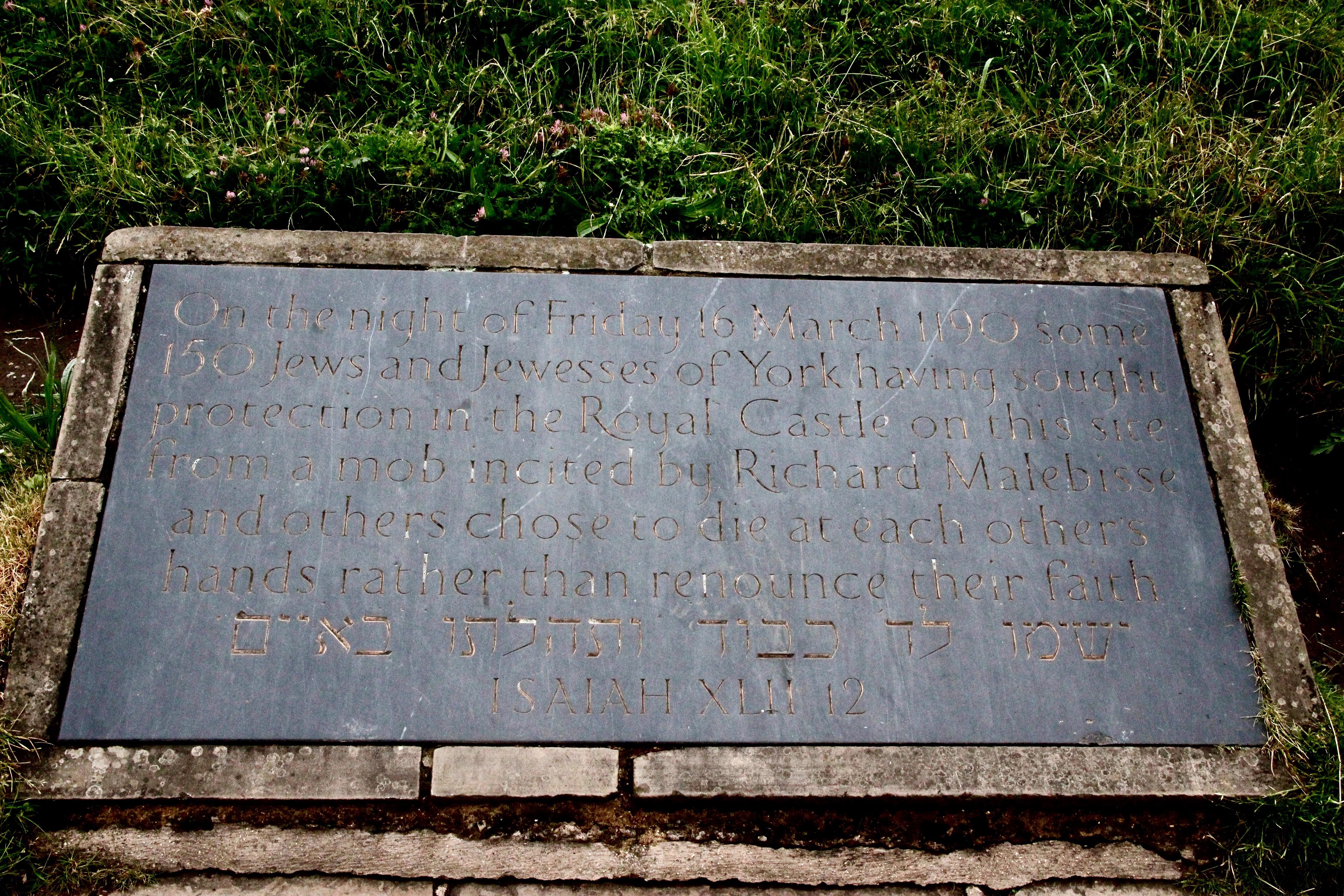

The first plaque commemorating the tragedy was installed at the foot of the mound in 1978. At present, a newer table stands here commemorating the victims. This table is not attached to the castle and it seems to be kept in a distance from the building as if it were not belonging to the attraction.

In 1995 daffodils were planted in a six-pointed shape on the mound - echoing the Star of David. This subtle memorial is noticeable only once a year when the daffodils are in bloom, and the visitor always has the choice not to see the memorial between the flowers. Most of the time the sides of the mound are covered with grass, and the gardening requires maintenance which does not always happen.

Nonetheless, despite the weak but existing commemorative efforts, the present site misses the agency which could let the visitor receive it as a part of 'hot interpretation'. The term 'hot interpretation' was introduced by David Uzzell. He suggests that there is a direct emotional way in which we can interpret experiences before or without thinking them over. This emotional engagement can be fired if the experience resonates with our personal past, nationalist feelings and community values, as well as ideological beliefs and convictions. According to Uzzell, the same is true when the visitors meet heritage sites. Beside the Clifford's Tower, Uzzell analysed WW2, WW1, Cold War and colonialist sites, and found that 'as time separates us from past events our emotional engagement is reduced'. In other words, the likelihood of emotional reactions in response to a heritage site depends on the time passed between the original traumatic event and the visit.

Source: English Heritage

I have analysed 1,799 TripAdvisor comments about the Clifford tower, and the results clearly show that the site was not interpreted emotionally by the visitors leaving a comment. Additionally, although an organised ghost tour stops here, it has not become a widely known dark tourism site either.

Is not experiencing the same emotionally overwhelming reactions as when visiting sites of similar tragedies only the question of the time passed? Or may there be other explanations which are not suggested by Uzzell?

For example, does the lack of physical authenticity changes our perception? Although the earth mound itself may still contain evidence from 1190, the current building was built a half century after a massacre. Do we focus too much on the architectural heritage that we tend to forget the genius loci, the spirit of place? Does it reflects our preferences towards the tangible over the intangible?

Or does the lack of emotional visits depend on our previous knowledge or lack of knowledge about the site, as well as on the interpretative attempts of English Heritage? Would the visitors' experience be different if English Heritage highlighted the story in the narrative of the site? Or is 'hot interpretation' a more cognitive phenomenon which does not provide enough time to evaluate the guides and information?

I still do not have conclusive answers to these questions. I hope a visitor survey in the future can contribute to our understanding of the sites where - similarly to the Clifford's Tower - temporally distant, but culturally significant conflicts happened.

Literature

Clark, J, (2010) Clifford’s Tower and the Castle of York. English Heritage.

Tunbridge, J. E., and Ashworth, G.J. . (1996) Dissonant Heritage: The Management of the Past as a Resource in Conflict. J. Wiley.

Uzzell, DL and Ballantyne, R. (1998) „Heritage that Hurts: Interpretation In A Post-Modern World‟ in DL Uzzell and R. Ballantyne (eds.) Contemporary Issues in Heritage and Environmental Interpretation: Problems and Prospects, London: The Stationery Office. pp 152-171.

Uzzell, D. L. (1989) „The Hot Interpretation of War and Conflict‟ in D.L. Uzzell (ed.) Heritage Interpretation: Volume I: The Natural and Built Environment, London: Belhaven Press.